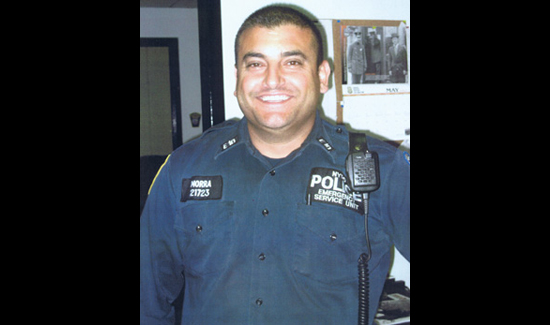

Compassion & Courage

“Treat them like you would your own mother, until they force you to do otherwise.” – Mike Morra

Law enforcement is a profession that attracts people with deep reserves of courage who are willing to take big risks for the people they serve, but the cops assigned to the NYPD’s Emergency Service Unit (ESU) take the notion of bravery to a different level. Nearly every incident they respond to is a high-risk, life-and-death scenario. They are regularly called upon to perform such tasks as dissuading a potential jumper perched on a high ledge, rescuing a child taken hostage, or freeing a family from the wreckage of a car accident. They will rush to help construction workers dying under scaffolding that collapsed or free severely injured office workers from an elevator that just plummeted forty floors.

Everyone in Emergency Service is a trained emergency medical technician, and every officer is a heavy weapons expert. A military background, especially a stint with the Marines or Special Forces helps, as does a basic knowledge of rope climbing, carpentry, and electronics. Staff are required to know the difference between a paranoid schizophrenic and someone with bipolar disorder and the appropriate tactics to use in each case. As one observer said, “ESU folks are out there doing God’s work.”

Officers bring a boy to safety after a tram was disabled over a NYC city street, dangling 250 feet above the East River. The youngster was trapped in the tram for almost 10 hours. It took the cops 12 hours to get everyone over to the rescue cage and back on the ground.

The physical demands of such specialized work require these officers to be extremely agile and able to remain calm under tremendous pressure. Considering the fact that ESU officers respond to lots of calls that require them to get up on top of bridges and skyscrapers, good balance is critical.

During his career, Mike Morra has dangled and rappelled off tall buildings and bridges scores of times. He remembers one man who was determined to end it all off an overpass in the Bronx. He almost succeeded, but Mike and his partner, Anthony Mazza, made it there in time. “We grabbed him just as he pushed himself off the ledge,” Mike said. “I had him by his belt and pants, and somehow we dragged him back up, which wasn’t easy. He weighed over three hundred pounds.” Since that incident in 2007, Mike has never missed a day of work, and no one has heard him complain, but his back still hurts and his doctor finally told him he may never be free of pain again.

It’s not easy to get assigned to the Emergency Service Unit. One year there were four thousand applicants for fifteen positions. Officers must be on the job for at least five years and have many, if not all, of the skills previously mentioned just to be considered. There are twenty-two tests, including exams for mechanical aptitude and agility. Mike’s family, including his father, was in the building trades, and his father had worked as an electrician. Mike was a serious runner, and months before the test he began swimming five times a week. “I did everything I could to score high on every one of those tests,” he said.

Most police officers never fire their guns during their entire careers. Every day, however, they negotiate and mediate often with desperate people in a rage or psychotic stated Mike’s always felt his job is to calm things down. “If I have to make an arrest, I tell a few jokes and, if I have to, a few fibs. If I can get them laughing on the way to Central Booking, I’m having a real good day.”

The fibs, Mike says, come in handy on any number of occasions. “If someone gets arrested late in the week, sometimes they get nervous if they realize they are going to spend the weekend in jail. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve said, ‘Hey, there’s night court today. Don’t worry. You’ll get out.’”

While a law enforcement career is often rewarding and exciting, there is a reason the job always makes the top five on any list of stressful occupations. The grueling pressure of shift work, working on holidays, seeing people at the worst moments of their lives, and coming face-to-face with heartbreaking cruelty and violence take its toll.

And there’s the endless paperwork. Everything a law enforcement officer does has to be written up and filed, sometimes in many places. The complexities of getting a warrant, which some say is the most important skill in law enforcement, can be mind-boggling. A thorough understanding of the law is required, along with how the law has been interpreted and the ability to make the case in writing. Any officer who has worked hard on an investigation, meticulously gathering the evidence and building a case against someone they know is breaking the law, only to fail when it’s time to get the warrant, will tell you it’s one of the most frustrating and disheartening parts of the job.

But even with all the violence and mayhem, Mike believed his most important weapons were his mouth and his brain. He’s still proud when he can control a situation with his wits rather than his firearm. And over time, cops learn to tune out abuse from the public. After a stop for speeding or a ticket for illegal parking, the outbursts of, “Don’t you have a terrorist to catch?” or “Isn’t there a bank robber you should be chasing?” or that old standby, “Don’t you know I pay your salary?,” rarely get a rise out of a cop who’s been on the job for a while. Yet there are times when even an easygoing and disciplined officer like Mike Morra gets annoyed.

Mike Morra and his three daughters on Halloween night, 2008. Left to right: Marina, Lianna, and Michaela. All the girls are showing a keen interest in sports.

Mike is still angry about the woman who came up to him when he was on patrol with a group of heavily armed officers outside Bloomingdale’s. It was ten months after the attacks of September 11.

“You could tell she was upset as she walked over to me,” Mike said. “She asked me what we were doing there. I told her we were part of a team that was working to stop another terrorist attack. She laughed. I asked her if she remembered 9/11, and she laughed at me again. She said there was no terrorist attack. September 11, she said, was a Bush ploy, an inside job. I pointed to the other officers who were there and said we had sworn to protect her and even give our lives for her. She just looked at me like I was crazy. She said, ‘Why would you do that?’

“Just a short time after dealing with that woman at Bloomingdale’s, I was patrolling on Wall Street. Along comes a group of men. They’re waving signs that the U.S. government had planned the attacks on the Trade Center. It’s hard to explain the emotions you go through dealing with people like that. I wanted to tell that woman at Bloomingdale’s and those guys on Wall Street that fourteen of my friends died saving people like them from those towers. They were really good friends, and they are gone. But about all I could do was tell them to move along, that if they interfered with traffic, I would lock them up. When I find myself getting emotional, I try to remember some good advice I got when I first came on the job about how to deal with all the nuts you meet on the street. Treat them like you would your own mother, until they force you to do otherwise.”

Excerpted from Brave Hearts: Extraordinary Stories of Price, Pain and Courage by Cynthia Brown, publisher of American Police Beat. Available at Barnes and Noble, Amazon, and at www.braveheartsbook.com.