The San Francisco POA

Despite hurdles, life is better for San Francisco cops

The San Francisco POA has 2100 active members currently serving with the San Francisco PD. You can scroll down to read about the history of the organization including the story of the time the members went on strike in 1975. Currently San Francisco officers are among the highest paid in the country with a starting pay of close to $90,000 and a 90% pension at age 55. Despite those numbers, the members voted down a recent contract that had a 6% raise over three years. Only half the members voted – 589 against, 569 in favor. Several officers said they rejected the pact because of a clause that would phase out the ability to take all unused sick pay in a lump sum at retirement.

Listen to former president Gary Delagnes speak to his members, the department and the community about the challenges the POA is taking on 24/7.

President’s Profile

Marty Halloran, President

San Francisco Police Officers Association

“I can’t say that working in the POA is always fulfilling. Our hard work and dedication to the membership is often undervalued and under-appreciated. That said, I continue to come to work each day hopeful and determined and I hold my head up at the end of each day’s effort, regardless of what is going, on knowing we are doing our best to improve the lives of San Francisco police officers.” – Marty Halloran

Martin Halloran became actively involved with the San Francisco POA in 1996 when he was asked to serve on the Scholarship and Community Service Committees. A committed union leader, he soon got caught up in aggressively supporting the mission of the POA. He walked the city’s precincts and talked to citizens about the importance of supporting legislation and candidates who were supportive of the San Francisco Police Department and he began organizing events to benefit the members.

After the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, Marty was appointed chairman of the San Francisco POA Trust Fund where raised money throughout the City to help New York City area law enforcement associations who lost members on that fateful day.

“Working actively in the POA has been an interesting personal journey,” Halloran says. “Despite all the hassles, I can say, in all honesty, that fighting for our members as they do the really hard job they signed on for, has enhanced my sense of duty, commitment and service.”

The SFPOA has 2100 active-duty members, and another 1000 retired. The association represents all ranks up to captain.

We welcome you to visit us online (http://www.sfpoa.org/) and check us out on Facebook.

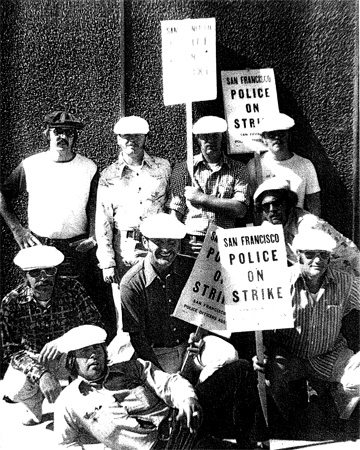

San Francisco cops go on strike

First police strike in city’s history

“San Francisco policemen receive only straight pay for overtime and no special rate for working nights, weekends, or holidays. Nor do they receive such benefits as fully paid medical, paid dental, educational incentive, longevity pay, Social Security, and other fringe benefits enjoyed by other city workers and by police in other cities. It was therefore a major shock when the Board of Supervisors chose to cut in half the standard pay raise which the police were scheduled to receive.”

This article was reprinted from The San Francisco Policeman, the official publication of the San Francisco POA, September 1975

San Francisco’s police have been criticized for going on strike because they are considered “different” from other jobholders. True, in their duties and responsibilities, and in the dangers and stresses they face daily, they are different. A policeman is subject to pressures experienced in very few other occupations.

It has been documented that the incidence of heart disease, severe depression, and other stress-induced illnesses is higher among police than among the general population, and that their marriages are more likely to end in divorce.

Police perform onerous, distasteful, dangerous work that often requires split-second judgment. with severe public condemnation or departmental censure if he fails. On the one hand he is expected to be beyond reproach strong, silent, and wise in every situation – and on the other he is an object of scorn for those in the society to whom he is a highly visible symbol of the establishment, and an object of ridicule in countless cartoons, TV shows, and motion pictures.

Others take out their frustrations on him, but he is expected to display no frustration at a time when police work, because of increasing crime and contemporary court practices, is more frustrating than ever. And what are policemen to do when they feel, and can clearly document, that they are not being fairly or adequately compensated for work performed?

San Francisco policemen receive only straight pay for overtime and no special rate for working nights, weekends, or holidays. Nor do they receive such benefits as fully paid medical, paid dental, educational incentive, longevity pay, Social Security, and other fringe benefits enjoyed by other city workers and by police in other cities.

It was therefore a major shock when the Board of Supervisors chose to cut in half the standard pay raise which the police were scheduled to receive. This shock, and its after-effects, must be viewed in the light of the policeman’s role in society today.

The police went on strike because of frustration and because of what they felt was unfair treatment by politically-oriented officials in an election year. But they recognize that strikes are not the most desirable means of settling a dispute, especially when an effective alternative exists – one that enjoys widespread acceptance in private industry and has proved to be a successful method of setting police wages in other major cities.

That alternative is collective bargaining with binding arbitration, in which the final decision is made by an independent, unbiased expert, who must take into consideration all the facts, including availability of city funds.

Among its advantages is the fact that it is conducive to realistic negotiation, rather than flat demands and ultimatums. San Francisco police will accept the most stringent anti-strike rule if the arbitration method is introduced for establishing policemen’s wages, benefits and working conditions in this city. No other anti-strike law will be necessary, and there will be no future threat of a strike.

Of our police, we ask the impossible

The first police strike in the history of the City of San Francisco has ended, but not without causing a deep and serious rift between the residents of this city and the police department. Sadly, many citizens and policemen, too, believe the trauma and ill-will generated by last week’s activities have driven a deep wedge between these two natural allies. It is this critical issue upon which we must now focus. Our primary responsibility must now be to come together—to rebuild and restore confidence and credibility in our police department and among our citizens. Frankly, it will be a difficult job, but one which must be accomplished. The reason for pursuing this course should be abundantly clear. The support and respect of every citizen is vital in fighting crime. Without it, police are waging a losing battle. I’d like to also emphasize a point which is often misunderstood.

No one has to be in law enforcement. I’d like to believe that those of us who are in law enforcement also believe in the dignity of the law and are dedicated to doing the best possible job. But all too frequently, policemen and policewomen are expected to do that which we do not require of ourselves. In the eyes of our citizens they must be above reproach, scrupulously honest, virtually without a fault. They must not make mistakes, and if they do, we criticize them unmercifully. We citizens expect policemen and policewomen to handle all situations with finesse, tact and competence. We expect them to risk their lives to apprehend lawbreakers. And we expect our officers to be enthusiastic, perform their jobs at top efficiency, and never complain or gripe (as we all do), yet we citizens refuse to take the time to acquaint ourselves with their working conditions at the district station or wherever they maybe.

If the streets of San Francisco are to be truly safe for all citizens—and that is the real issue—not only po1icemen but citizens must accept the responsibility that law enforcement is everybody’s business. Through a strong relationship of mutual trust and respect, everyone can win. Cooperation, not dissension, is the key to this effort.

Statement by Marvin Cardoza, president, San Francisco Police Commission

“In 1972, the first slate of Bluecoats was elected at the San Francisco POA.. The president was Jerry Crowley who would become one of the most commanding and effective leaders – some would say infamous — in the organization’s history. No more were the monthly meetings mere gabfests held over a corned-beef and cabbage buffet. Meetings under the Bluecoats became boisterous, often contentious, table-pounding sessions of grievance, strategy and debate.”

The San Francisco Police Officers Association was incorporated in 1946. In the early years, it served as a fraternal/social organization, and did not actively engage in political campaigns, nor did it solicit for better wages and benefits on behalf of its members.

In 1953, the Association took its first foray into the political realm when it secured a city charter amendment that established a survey formula for determining police officer wages. This was very significant because prior to this any police or fire wage increase – regardless of how much it was — had to be approved by a citywide ballot imitative.

The years between 1968 and 1974 are significant as the POA tested the political waters several more times and gained significant pension upgrades by way of ballot proposition.

In 1970, the POA experienced a real sea change. That year, a group of outspoken and politically savvy officers formed a sub-group within the Association with the intent to aggressively campaign and negotiate for better wages, benefits, and working conditions. That group called themselves The Bluecoats.

In 1972, the first slate of Bluecoats was elected to run the SFPOA. The president was Jerry Crowley who would become one of the most commanding and effective leaders – some would say infamous — in the organization’s history. Following the election of the Bluecoat slate into office, the Association was completely transformed from a social organization into a legitimate employee rights organization. No more were the monthly meetings mere gabfests held over a corned-beef and cabbage buffet. Meetings under the Bluecoat agendas became boisterous, often contentious, table-pounding sessions of grievance, strategy and debate.

In 1975, San Francisco police held the first labor strike by a big city police department since the Boston Police Strike of 1919. The SFPOA, led by Jerry Crowley and the Bluecoats, led its members out of the stations and onto the picket lines. The San Francisco Firefighters joined in the strike, which lasted for three chaotic days before a settlement was reached with Mayor Alioto and the Board of Supervisors.

The short-term gain was an impressive 13% salary increase. (One which was due to the cops and firefighters through a salary formula, but which was not being honored by the civic leaders of the day.)

The long-term fallout was significant. Soon following the strike, San Francisco voters created a lesser Tier II pension system, dissolved the previously enacted salary survey, and destroyed all vestiges of public support and confidence in the city’s first responders. It took nearly 20 years of hard campaigning and fence mending to improve the deficient Tier II Retirement that, even today, stands inferior to that system which was in place prior to the strike.

In 1992, the POA successfully campaigned for and secured the city’s first collective bargaining agreement with police and fire. This milestone achievement is still on the books and has yet to be invoked by either side of the bargaining table, but stands as a last, best effort bulwark against abuse to police and fire who are now prohibited by law from striking.

Today, the SFPOA enjoys a respected cooperative working relationship with civic leaders, and sees the highest public opinion poll numbers in its history. Since the mid1980s, when the SFPD was ranked 92nd in the state in wages and benefits, the POA leadership has crafted significant gains. Today, The San Francisco Police Department is the highest paid in the state by margins as high as 22%. Nearly bankrupt and insolvent in the early 1990s, the SFPOA is today a financially healthy organization with multiple investments and holdings. It operates on a $3 million annual budget, and reports more than $12 million in assets.

Since inception, the SFPOA has had 26 presidents, including its current leader, Martin Halloran. Martin has succeeded Gary Delagnes, the longest-serving POA president, and considered the person who engineered some of the Associations most significant gains.

As Martin Halloran leads the Association forward, he can see looming issues on the horizon, including the cost of health care, and the continued assault on public safety workers’ pensions and benefits.

Connect with us

Connect with us on the following social media platforms.