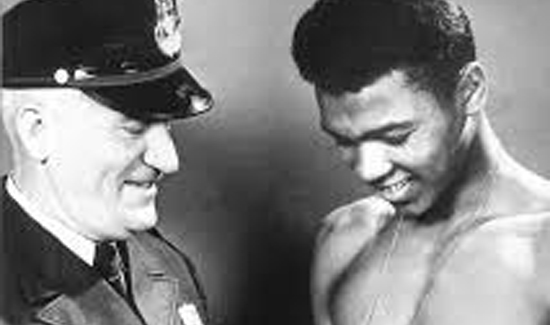

Louisville Cop Gave Ali His Start

Muhammad Ali and Officer Joe Martin, who took the young Cassius Clay under his wing after his bicycle was stolen when he was 12-years-old.

Most people know the story of the police officer who helped a distraught 12-year-old boy after his bicycle was stolen. It was Louisville Police Officer Joe Martin who encouraged Cassius Clay to come to his boxing club and give the sport a try. The rest is history.

Scroll down to read Officer Joe Martin’s obituary with comments from Ali about the crucial impact the officer had on his life.

“The messages have come in every language, from every corner of the globe. From wherever you are watching, know that we have been humbled by your heartfelt expressions of love. It is only fitting that we gather in a city to which Muhammad always returned after his great triumphs. A city that has grown as Muhammad has grown. Muhammad never stopped loving Louisville, and we know that Louisville loves Muhammad. We cannot forget a Louisville police officer, Joe Elsby Martin, who embraced a young 12-year-old boy in distress when his bicycle was stolen. Joe Martin handed young Cassius Clay the keys to a future in boxing he could scarcely have imagined. America must never forget that when a cop and an inner-city kid talk to each other, then miracles can happen.” – Lonnie Ali, speaking at Muhammad Ali’s funeral.

Via the New York Times:

Joe Elsby Martin, 80, Muhammad Ali’s First Boxing Teacher

by IRA BERKOW

Published: September 17, 1996

One rainy night in 1954, Joe Elsby Martin, a Louisville, Ky., policeman who ran a local recreation center called the Columbia Gym, saw a skinny 12-year-old boy with tears in his eyes come into the gym seeking him out.The boy was distraught because his new red Schwinn bicycle, a Christmas present from his father, had been stolen. He had been told that a policeman named Martin would fill out a police report for him.

”What’s your name?” Martin said.

”Cassius Clay,” the boy said, adding angrily that he would whip the thief if he could find him.

Martin then asked the young Clay if he could fight, saying, ”You better learn to fight before you start fightin’.”

In this way did Martin, who died at his Louisville home on Saturday at the age of 80, launch the boxing career of Muhammad Ali, an Olympic gold medal champion, a three-time world heavyweight boxing champion and a controversial and often beloved international figure.

In his autobiography ”The Greatest: My Own Story,” written with Richard Durham, Ali recalled his meeting with Martin and introduction to boxing.

”I ran downstairs, crying, but the sights and sounds and the smell of the boxing gym excited me so much that I almost forgot about the bike,” Ali wrote. ”There were about 10 boxers in the gym, some hitting the speed bag, some in the ring, sparring, some jumping rope. I stood there, smelling the sweat and rubbing alcohol, and a feeling of awe came over me. One slim boy shadowboxing in the ring was throwing punches almost too fast for my eyes to follow.”

After the lad had written out the report and was about to go, Martin tapped him on the shoulder. ”By the way,” he said, ”we got boxing every night, Monday through Friday, from 6 to 8. Here’s an application in case you want to join the gym.”

The boy had never worn a pair of boxing gloves, but was excited about trying the sport.

”When I got to the gym,” Ali wrote, ”I was so eager, I jumped into the ring with some older boxer and began throwing wild punches. In a minute my nose started bleeding. My mouth was hurt. My head was dizzy. Finally someone pulled me out of the ring.”

”Get someone to teach you,” a slim welterweight told the young Clay.

And that someone was Martin. He had worked for years with amateurs and had been instrumental in integrating Louisville’s amateur boxing, combining separate gyms for black and white fighters. While Martin was not a professional boxing trainer, he knew enough of the rudiments of the sport to get the young Clay started.

”He could show me how to place my feet and how to throw a right cross,” the fighter later wrote. And while Clay threw wild punches, ”something” was driving him. ”I kept coming back to the gym.”

Martin told him: ”I like what you’re doing. I like the way you stick to it. I’m going to put you on television. You’ll be on the next television fight.” At that time, Louisville amateur fighters, some from Martin’s gym, appeared on a weekly televised boxing card called ”Tomorrow’s Champions.”

”Thrilled at the idea of being seen on TV all over Kentucky, I trained the whole week,” Ali said. ”They matched me with a white fighter, Ronny O’Keefe, and I won my first fight by a split decision.

”All of a sudden I had a new life.”

Martin’s tutoring helped the young Clay win six Kentucky Golden Gloves titles and two national Amateur Athletic Union titles leading up to the 1960 Olympics in Rome, where Martin was a coach and where the fighter won the heavyweight gold. After Ali turned professional with the backing of some businessmen, Martin continued to train amateurs and remained active with Golden Gloves, serving for a time as the Kentucky representative on the organization’s national board.

In all, he held the Kentucky Golden Gloves franchise for almost 40 years. In 1977, he was inducted into the Amateur Boxing Hall of Fame.

A police officer for 34 years, Martin did some auctioneering after retiring from the force. In 1980, Ali appeared in a sparring exhibition to raise money for Martin’s campaign for Jefferson County sheriff, but Martin lost in his bid to win the Democratic nomination, the second time he was defeated for that post.

Martin is survived by his wife, Christine; a son, Joe Jr., and a granddaughter.