“It Was Like Looking Into Hell”

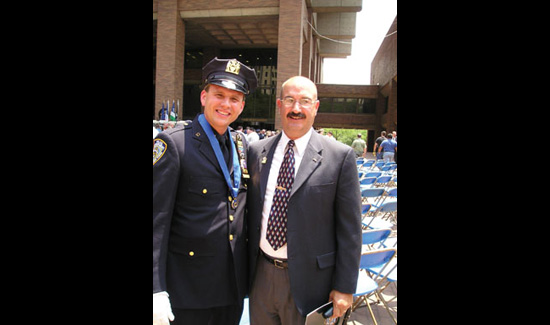

John Busching (left) with John McLoughlin on June 16, 2004 at Medal Day at NYPD Headquarters. McLoughlin, a former Port Authority police officer, was the last person to be rescued alive from the rubble at Ground Zero. Busching was one of the people credited with saving McLoughlin’s life.

“True heroism is remarkably sober, very undramatic. It is not the urge to surpass all others at whatever cost but the urge to serve others at whatever cost.” – Arthur Ashe

In the fall of 2001, New York City was home to over eight million residents as well as more than a half-million commuters who made the trek in every day to go to work. With close to 60,000 employees, the New York City Police Department is the largest law enforcement agency in North America and bigger than most countries’ standing armies. New York cops witness more in a week than most of us will see in our lifetimes.

The thousands of NYPD officers who raced to Ground Zero were overwhelmed with the enormous loss of life and the catastrophic devastation after every one of the seven buildings in the huge World Trade Center complex collapsed. But there was something else that was hard to deal with.

Only 20 People to Rescue

Wherever they work, law enforcement officers are the consummate rescuers. Nothing pleases them more than to lock up bad guys who prey on innocent victims. To find themselves in the middle of the worst crime scene in United States history—an attack that took the lives of close to three thousand innocent people including 341 firefighters, 2 FDNY paramedics, 6 volunteer hospital EMS workers, 37 Port Authority police officers, and 23 members of the NYPD—and have no witnesses to interview, no one to arrest, and only a few people to rescue, was not only frustrating and disorienting but profoundly depressing as well. The hijackers were dead, and only twenty people would be pulled out alive after the towers fell.

* * *

On that clear September morning, John Busching had been at home getting ready for work when the first plane hit the North Tower at 8:46 a.m. John said it wasn’t much past 9 a.m. when a friend, Detective Louie Franco, called and told him to turn on the television. “I had just turned on the TV when the second plane hit. I sat there stunned, looking at the screen. I had responded to the Trade Center bombing in 1993 and knew how bad that was. It was obvious this was going to be much worse.”

He knew Floyd Bennett Field, headquarters for Emergency Service, would be open. He gathered a change of clothes, kissed his wife and three-year-old son good-bye and rushed out the door. The roadway, usually jammed with traffic at that time of day, was eerily quiet. As John drove toward Floyd Bennett, he saw a Port Authority SUV ahead. “I went right in behind him,” John remembered. “When I got closer, I recognized the driver’s face in the sideview mirror. It was George Howard, a Port Authority cop I knew. We’d trained together for the Police Department and the Volunteer Fire Department in my town. I tried to get his attention, but he didn’t see me.”

John turned off at Flatbush Avenue. He found out later that day that Howard arrived in Lower Manhattan just as the first tower fell, at 9:59 a.m. He was crushed to death by a falling air conditioner. Four months later, at his State of the Union address, President Bush held up George Howard’s badge as he spoke to the nation about the sacrifice made by cops and firefighters on that terrible day.

When John pulled into the parking lot at Floyd Bennett, it was almost empty. He walked across the road to Aviation where he found a group of officers talking about the “high-rise rescue plan.” It would be a joint operation, developed in the early 1980s, between the NYPD’s Emergency Service Unit and the Fire Department. Firefighters would bring the people who were trapped in the burning towers up onto the roof after Emergency Service cops, carrying high-powered saws, bolt cutters, and medical supplies, rappelled out of helicopters down onto the roof and cut down the vast array of transmission antennas so the aircraft could land and begin to evacuate the victims.

The cops in the room had no way of knowing the immense fireballs ignited by the eight thousand gallons of fuel that came gushing out of each airplane after impact caused the temperature on the roof to soar to thousands of degrees Fahrenheit. It was 9:59 a.m., and they were ready to head out when the 110-story South Tower of the World Trade Center fell. In less than one minute the South Tower collapsed into a mass of dust and rubble. The North Tower came down at 10:28 a.m. Before it was over, seven buildings and almost fourteen million square feet of space had been transformed into a vast wasteland of twisted steel, concrete, and dust.

Back out at Floyd Bennett Field, the ESU team came up with a new plan. They would transform their two big Bell 412 helicopters into a flying hospital, a sort of air ambulance as one officer described it. One of the commanders decided there would be one paramedic and one EMT in each helicopter. All four would be Emergency Service officers. They knew there could be up to fifty thousand people working at any given time in those towers. The buildings had fallen, but they still hoped there would be a lot of lives to save.

It was a relief for the four officers, EMTs Tom Kirklava and Tony Conti and paramedics Darrell Summers and John Busching, to have something to focus on. They were all anxious to get to the site and get to work.

“We sat there making our plan when the Commander, Deputy Inspector Joseph Gallucci, came into the room,” John said. “The Inspector had a strange look on his face. He was very somber and serious. He told us, almost apologetically, that we would not be taking people out. We all sat there dumbfounded. Finally I asked if we shouldn’t try to land or be lowered onto whatever top floor is left? He just looked at us and said, ‘There is nothing left.’ “We all knew then how bad it was. We were going to lose a lot of our friends.”

John’s premonition was accurate. Throughout the day, reports kept coming in about friends and coworkers who were injured, missing, or dead.

It’s hard to explain how difficult it was for that roomful of cops to accept the fact that they weren’t needed, that they would not be able to rescue people from the rubble, that there would be no need for medivacs. “I remember it took longer for the more senior guys to come to terms with it,” John said. “One of them just couldn’t comprehend it. He kept repeating over and over, ‘We gotta get in there. We gotta get in there.’”

The New York City Police Department runs like a well-oiled machine when catastrophe occurs. Despite the fact that cell phones weren’t working and communications had broken down between the Fire and Police departments, the NYPD chain of command remained intact. The officers at Floyd Bennett were told by the Commander of Aviation to stay put until they heard from Headquarters. Finally the word came down. The officers were to be flown by helicopter to Lower Manhattan. They would get their orders once they landed.

As they approached Battery Park, the officers looked down on the smoke billowing up hundreds of feet in the air from the rapidly spreading fires. The area where the towers had fallen looked like a nuclear bomb had been dropped. Once they landed, the ESU officers were met by the Commanding Officer of the Emergency Service Unit, Inspector Ron Wasson. Scores of firefighters and ESU cops were showing up, and Wasson split up the officers arriving on the helicopters into two teams.

Search for Two Buried Cops

For John and his colleagues, it was a relief to finally have something useful to do. They gathered every portable rescue tool they could carry and began heading to the pile to begin their assigned tasks. “We’d only been working for a few minutes when the orders changed,” John said. “We were told to move fast to assist an ESU rescue team that was working to free two Port Authority police officers. They were buried in the rubble. They were still alive, but nobody had been able to reach them.

“We were told to get our gear and meet up with a search team that was waiting for us somewhere between Three, Four, and Five World Trade,” John continued. “There were fires everywhere and they were spreading. We were trying to figure out where our group was gathering when we saw several firefighters and some ESU cops staggering down off the pile. They were covered from head to foot with grime and a coat of thick white dust. You could barely see their faces. They looked completely wiped out, mentally and physically. One of the guys was the other medic I rode with on the helicopter. He started to walk in my direction but when he was only a few feet away, he passed out and collapsed on the ground. He was a really big guy but a couple of people were able to pick him up and bring him to a medical aid station.”

John remembers the conversation was focused on getting to the two buried cops. “I remember hearing someone say they had a better idea of how to reach them,” he said. “Someone else said one of the cops needed an IV. I felt good because I had that with me.”

John’s team was split in half and his group was ordered to stay in the back. His Captain, Gin Yee, radioed to Sergeant John English, who was up on the top of the pile. Sergeant English knew John was a paramedic and would have his medical kit with him. “I could hear him up there yelling to send me up,” John said. “I wasn’t sure what to think. I had just seen a really big guy collapse in front of me. The smoke was so thick you could barely see. There were fires everywhere. Everyone was telling me not to go up to the top of the pile. It was too dangerous and I wouldn’t be able to do anything. But Sergeant English was calling. I didn’t have a choice.”

Once John decided he would try to climb to the top of the pile to see if he could help, he had to stop and think. How would he get up there and what would he find? The pile was a massive wreck of crushed concrete blocks and steel beams. The whole place was a smoldering, smoking fire. He would have to crawl along the beams and hope he didn’t fall into the abyss below.

“It was like looking up into hell,” John remembered. “Dante’s Inferno could not have been worse.”

“I thought about what I might encounter. I crawled up the pile. It took about fifteen minutes to reach Sergeant English after climbing up and over large amounts of debris and avoiding voids that dropped from a few feet to more than sixty and seventy feet down. When I got to the top, the Sergeant told me I was going to be sent in to give the trapped Port Authority cop some medical attention. He told me he had been buried at least thirty feet down. No one had been able to get to him.”

English told John he would have to shimmy down a steel I-beam from the top until he hit the concrete flooring. Then he’d have to squeeze down another couple of feet where a Battalion Chief from the Fire Department would be waiting. The Fire Chief would guide John the rest of the way in.

“Climbing down the I-beam, I had to pass under two pieces of concrete flooring that had formed a tent,” he remembered. “I didn’t want to fall off that beam on the right side. It looked like a really long drop.”

When John found the Battalion Chief, a paramedic from the Fire Department was already there, but he had gone down without his medical bag and the trapped officer needed an IV. “He offered to try to get to him first to see what the trapped officer needed,” John said. “I told him it wasn’t necessary, that I was a paramedic and I had my equipment with me.”

It’s no secret that in New York City there’s an intense rivalry between the Police and Fire Departments, and the animosity can be particularly intense between firefighters and ESU cops who frequently respond to the same disasters. John said it really hit home that we were dealing with a very unusual event when the Battalion Chief announced he was sending John down, not one of his own guys from the Fire Department. “I remember standing there thinking, ‘Oh man, if he wants me to go, this must be the end of the world.’”

The Fire Chief instructed John to focus on what he was doing and block out everything that didn’t have to do with the mission. Then he told Busching to hand over his medical kit. He said the pathway to the officer was so small the medical kit might impede his progress. John would have to crawl down on his stomach. There was no room for the kit.

John thought for a moment trying to figure out what he should do when another ESU officer, Eddie Reyes, crawled out from the hole. “When he saw I had no one with me, he volunteered to go in behind me,” John said. “Eddie Reyes was a registered nurse, but the Fire Chief didn’t like the idea. Eddie had just come out after twenty minutes of exhausting labor, and he didn’t look well. But Eddie insisted he wanted to go with me, and I was relieved to have some help.”

John handed his medical bag to Reyes and got down on his stomach. As he began to inch his way over to the injured officer, he had to exhale deeply to pull himself through the small space. He laid on his stomach and crawled twenty-five feet. When he came across another steel beam laying across his path, he had to exhale even harder to squeeze under it.

Buried Under Massive Chunks of Cement and Steel

Finally John saw the man. He was lying face down and completely buried under massive chunks of cement and steel. From his waist down to his feet, he was completely crushed under the rubble, but he was still conscious.

“He told me his name was John McLoughlin,” John said, “and that he was a Port Authority cop. He’d had some medical training, so he knew the situation was bad.”

John, wife Chris, and son Joseph enjoying a vacation in upstate New York, 2008. When John made the decision to try and rescue Port Authority Officer John McCloughlin, he believed he would die and never see his family again.

At that moment John Busching began to face the fact that he was probably going to die. “The most you could move was to push yourself up a couple of inches,” he said. “You couldn’t move to your left or your right.” John thought about his wife and son at home and realized he might never see them again. As he began to inch his way out, John looked over at McLoughlin and realized there was no way he could leave him there. “I couldn’t do it,” he said. “I stopped backing out. I remember thinking, ‘I’m screwed, but I have to crawl back and stay with him.’”

John inched his way back to McLoughlin and tried to come up with a plan. The hole measured about three feet across and was eighteen to twenty-four inches high. Due to the tight quarters, only one rescuer at a time could have direct contact with him. There was no natural light, and when the wind shifted, putrid smoke filled the hole where the rescuer was positioned. Everything was burning and collapsing. The space where McLoughlin was trapped was next to an elevator shaft. John says there must have been an updraft of air in that spot because no one remembers McLoughlin complaining about the smoke.

Once Busching made the decision to stay, he approached the task like everything he decided to take on, with total discipline and the expectation that everything was going to be okay. Eddie Reyes came back with John’s medical supplies. Eddie crawled in behind him, but the space was so small the cops were worried there might not be room to get the IV out of the bag. McLoughlin was nauseous and getting dehydrated, and John knew he had to start an IV and get him some fluids soon. “A doctor at the top of the hole told me I could give four milligrams of morphine and I wanted to get that going too, but my hands were trembling pretty badly. That’s not good for starting IVs. I remember thinking, God, I’m going to need some help. But for some reason, right at that moment, my hands stopped shaking and I was able to get the IV into McLoughlin’s arm on the first try.”

McCloughin was in enormous pain, but John never could get him the morphine. It came in a delivery system that wouldn’t fit in the IV tubing. “McLoughlin didn’t want it anyway.” John said. “He thought it would cause his blood pressure to drop and he would die.”

“Once the IV was working, Eddie began backing out and I inched my way backward behind him. I was face down the whole time sucking in my breath to make myself smaller. To get from where McLoughlin was buried back up to the top of the pile took about twenty minutes, but it seemed like hours.”

When John finally got himself back to the top of the pile, he spoke to John Chovanes, a former EMT and doctor who’d had a lot of experience treating trauma victims. When Chovanes realized the towers had fallen, he got in his car and drove to Lower Manhattan from his home in Pennsylvania. The doctor was alarmed when Busching described McLoughlin’s condition. “Dr. Chovanes decided to go down and give him some morphine,” John said. “When the doctor came out, he had the same look as everyone else who had gone down there. Absolute horror.”

Chovanes and John decided to take turns going back down to try to keep McLoughlin alive. When Dr. Chovanes crawled out after his fifth trip down, he was visibly distraught. The doctor told Busching if McClaughlin’s condition deteriorated any more, they would have to amputate both his legs. When John asked Chovanes how he could possibly take off his legs down in that hole, he replied, “I’m a surgeon, so I have to do it. And you’re the only one around who has medical training, so you have to help me. I’ll come up with a way to get his legs off. You look in your bag and figure out how to keep him from bleeding to death.”

John was aghast at this prospect but he rummaged through his bag and came up with cloth triangular bandages to make tourniquets. The doctor took one look at the bandages and said there was no way that would work. He needed to find something else.

“Chovanes asked me if I had any clamps.” John said. “He’d been a paramedic and he knew we don’t carry clamps. He told me to keep thinking. Like every ESU cop I had a Leatherman tool that looks like a small pair of pliers on my belt. When I asked if that would work, the doctor seemed relieved. He told me he knew I would come up with something.”

Chovanes had a plan, but when John heard what it was, he felt nauseous. The doctor said if things got critical, he would have to take McLoughlin’s legs off with a cordless saw. “You,” he told John, “will clamp the wounds closed with your Leatherman tool.” The doctor said they would not be able to anesthetize him, it would be too dangerous.

“I decided right then, there was no way this was going to happen,” John said. “When I told the cops and firefighters who were digging that if we couldn’t get him out soon, we were going to amputate his legs, they began to dig a lot faster.”

As they were making plans to save John McLoughlin’s life, a team of thirty people were being rotated in to dig him out. The only tools they could use were their bare hands. They had to dig under the trapped officer. Everything above him was a solid mass of concrete and steel. About thirty firefighters and ESU cops made up the team. Two firemen and two cops worked fifteen-minute shifts before being relieved. It took almost twelve hours. They dug out John McLoughlin one handful at a time.

The Port Authority officer was crushed at ten in the morning on September 11. When the last piece of concrete was removed from under his body and there was enough room to slide him out, it was seven o’clock the next morning.

“They brought him out in a Stokes basket, which is a kind of metal stretcher,” John said. “A long line of firefighters and cops, going all the way back to Church Street, passed the stretcher from one person to the next until the severely injured officer reached the waiting ambulance.” John Busching said watching John McLoughlin brought out of that hole alive is the most remarkable thing he ever witnessed.

John with his tactical-medical sack. John had to replace the bag he carried with him when he crawled 30 feet down into the wreckage of Ground Zero right after the attacks of September 11 to give Port Authority cop John McLoughlin life-saving help. The bag, he said, was damaged beyond repair. He replaced it two days later on September 13, 2001.

McLoughlin was in a coma for over a month. The doctor in charge of the trauma team overseeing his care told John Chovanes and John Busching they saved his life. When someone is crushed, they must be treated before they are freed. Otherwise, once they are unencumbered, all the toxins will be released when the pressure is relieved, and death is nearly always the outcome. John and Chovanes were aware of this and had given McLoughlin sodium bicarbonate, which neutralized the acidic toxins in his body. It was only fifteen minutes of paramedic training, but John had just read an article about the subject in a medical journal and, luckily for John McLoughlin, he remembered it.

McLoughlin now lives in Upstate New York. His life since that day has been an arduous series of surgeries, followed by grueling and painful physical therapy. He lost a lot of his muscle mass due to the extended time he suffered without oxygen. He had to learn to walk again using a set of different muscles.

John says they bump into each other every once in a while and McLoughlin seems very happy to be alive. He has four children, volunteers with his son’s Boy Scout troop, and even helped someone get through a similar rehab program by providing inspiration and encouragement.

Oliver Stone’s film World Trade Center revolved around John McLoughlin’s experiences on September 11. At some point during the filming, McLoughlin called John Busching and asked if he wanted to work on the film. “I told him it’s whatever you want. You were the victim. It’s your story.”

John did go out to Los Angeles for a couple of weeks to give technical advice on how things should look. But when it came time to edit the movie, the role John Busching played saving John McLoughlin’s life ended up on the editing room floor. But John has no complaints. “Oliver Stone was really great about the whole thing,” he said. “He told me he couldn’t be sure how the film would play out, that there were a lot of firemen, medics, and cops and that some scenes might get redundant. I didn’t have any problem with that.”

John worked twelve-hour days for three solid weeks at Ground Zero. Some days, he says, were better than others. Day after day of searching for their dead colleagues, finding nothing but piece of flesh or a small body part that had to be packaged up and sent to the morgue, took a toll on everyone there.

“When you were at Ground Zero, you had to isolate one task and focus on it,” John said. “But if you looked at the whole scene, you could go crazy. There was no way any one individual could do much on their own. You had to focus on small, manageable jobs.”

Everyone involved with the tragedy says looking back it was the funerals that prolonged the grief. A total of 409 first responders died, and everyone had a separate funeral. As one officer pointed out, to have gone through an experience like that and be around that much grief was extremely depressing. “You could never get over it,” he said.

John said his brother, a firefighter, took it worse than he because of all the funerals. “I guess everyone did the best that they could, but it was really tough. It is a testament to the city that we had very few suicides. I think there was only one EMT who took his own life. That is a quite a tribute to the toughness of New Yorkers.”

* * *

John Busching has a favorite expression. When he’s delivered a baby, rappelled out of a helicopter, or crawled inside the smoldering wreckage at Ground Zero, his buddies say they often hear him saying, “It’s really something.”

When you get to know John, you understand that despite the tragedies, the bureaucracy, the paperwork, the endless rules and regulations, and the tragedy of September 11, he still believes that being a cop in New York City is the greatest job in the world. And how many people do you know who after twenty years at the same job are still saying, “It’s really something,” when they talk about their work?

Excerpted from Brave Hearts: Extraordinary Stories of Price, Pain and Courage by Cynthia Brown, publisher of American Police Beat. Available at Barnes and Noble, Amazon, and at www.braveheartsbook.com.