“We Searched Everywhere. We Never Found Anyone.”

September 11, 2001: A Look Back

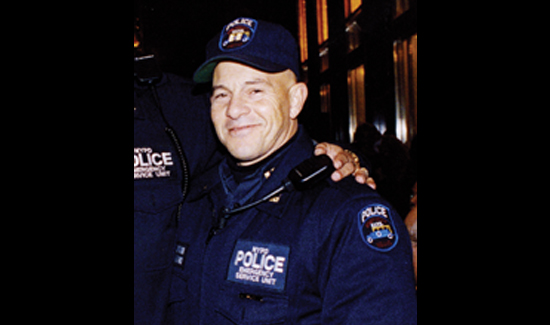

Barry Galfano, who retired at the rank of captain from the NYPD, was considered one of the nation’s leading experts in the care and training of police dogs. Once Barry learned he would be the commanding officer in charge of the care, health and job performance of fifty dogs working in the NYPD’s Canine Unit, it was the fulfillment of his life-long love affair with police dogs.

When Barry was just 10 years old, he began training his first German Shepherd. “I wanted him to be just like Rin Tin Tin,” he said. The basic course for police dogs and their handlers is sixteen weeks. Training the dogs to find dead bodies, narcotics, and other search and rescue tasks takes another twelve weeks—that’s a total of twenty-eight weeks, almost a half year. Barry supervised all the dogs who responded to the attacks in NYC on 9/11.

Barry’s long hours at Ground Zero over the span of many months is the reason, his doctors say, he got cancer. After a superhuman struggle against the disease, Barry finally succumbed to his illness on June 26, 2011.

Here’s a video of what Barry had to say just weeks before he died (WARNING: May be disturbing to some readers):

Here’s Barry’s 9/11 story – the work that took his life:

When his alarm rang on September 11, 2001, Barry was looking forward to his day off. He planned to make a fast trip to the gym to work out, come back home for a quick shower, then go to a nearby beach for a run. He was training for an upcoming race, and it was a perfect day for a long run.

He was just about to turn into his driveway after working out at the gym when his police radio started to crackle. “There was lots of noise—something about a small plane crashing into one of the buildings at the World Trade Center. I remember thinking, wow, how could that happen?”

Experienced law enforcement officers know when something big is happening by the sound of the voices on the radio. When Barry heard the frantic voices of the operators going back and forth trying to get information, he knew there was no way he was going to the beach that day. He ran into the house and turned on the TV just in time to see the second plane hit the South Tower.

After the shortest shower of his life and a couple of swipes with a towel, Barry threw on some clothes and drove to Floyd Bennett Field, headquarters of the Emergency Service Unit. His wife was at work. Two of his four kids were in school. His oldest daughter was still living at home and teaching at a local elementary school. His oldest son was serving in the Navy in the Special Forces. Barry never thought to leave a note.

Barry was a Captain in charge of the NYPD’s K-9 Unit, but he was new to the Emergency Service Unit, and he had not gone through search and rescue training. He felt understandably anxious about what awaited him as a high-level supervisor at a major disaster where he knew ESU cops would take the lead.

When Barry learned he had cancer, his family and friends were a constant source of support. “But no one was there for me more than Jackie,” Barry said. “She’s a cancer survivor herself and she knew what I was going through. Her love and support never wavered.” Jackie Bourne is a lieutenant assigned to the NYPD’s 70th Precinct in Brooklyn.

When Barry got to Floyd Bennett, he changed into his uniform and drove into the city over the Manhattan Bridge. “I’ve crossed this bridge hundreds of times on my way to the city,” he said. “There is one point—around the middle—where there is a clear shot of the two towers at the World Trade Center. Just when I reached that spot, I saw there was just one tower standing. It’s hard to explain what that was like. My mind was racing. I knew I’d seen something big, but I didn’t understand what it was. The noises coming over my police radio were unlike anything I had ever heard. The dispatchers did an incredible job trying to keep everyone calm. They were trying to collect information, but chiefs were screaming for units, and everyone was cutting off one another. I remember one operator kept asking the same thing over and over. ‘The building came down? The building came down?’ Listening to that operator, I thought the world might be coming to an end.”

Barry was driving down the West Side Highway when the second tower fell. “When I couldn’t drive any farther, I ditched my car. I left it in the middle of West Street and started running through the streets toward the Trade Center. I finally found an ESU cop. When I told him I was the new Captain, he just looked at me and said, ‘Well, welcome to ESU. Here’s some goggles. You’re going to need these if you want to see anything.’ I put the goggles on and followed him in.”

As he got closer, Barry’s first impressions were surreal. “I’m a skier, and all I could compare it to was fresh snow on a mountain after a heavy snowstorm. There was over a foot of ash. It came up to my knees.”

He tried to focus. “By this time we all knew it was no accident. My training taught me that the first attack is usually a diversion. Once all the resources are tied up at the first incident, they hit you again. The second attack would be much worse. When I looked around, I knew I would not make it home that night, but I decided I would do my part to try and stop whoever did this to us from hitting us again.”

Barry took his lead from Mike Curtin, a sergeant with ESU. “Mike was a Marine, and he was very conscious that there might be more attacks. He went tactical with heavy weapons. So did I.”

Barry gathered a group of officers together. He told them to keep searching for victims but also be aware that a second wave of attacks could kill even more innocent people. “We were thinking there was a good possibility that whoever was behind this could be heavily armed and ready to attack us as we were looking for victims. I told them to keep searching but keep their eyes open. I fully expected a ground attack with suicide bombers and AK-47s. I was ready to stop them.”

Two cops with dogs and three ESU cops armed with Heckler & Koch MP5 submachine guns that fire thirty rounds at a time checked the perimeter of the site to make sure there were no observable threats. After that they began coordinated patrols in hopes their heavy weapons and presence might prevent another attack.

As hours went by, Barry realized they were going to be there a long time.

* * *

The search for bodies went on for nine months. Regular patrol officers worked two consecutive days at Ground Zero and then were rotated out back to their regular assignments. Emergency Service officers were there every day.

The massive cleanup effort eventually involved hundreds of construction workers, ironworkers, and crane operators. “The first couple of days did not go well,” Barry said. “It wasn’t until the cranes arrived that things started to happen. The crane operators learned quickly that this was a massive crime scene with a lot of victims, and they would not be able to clean it up quickly. It was amazing to watch them lift up a bar of steel and be so careful. They were so respectful once they knew there might be dead bodies there. Anybody who was down there will tell you those crane operators were a godsend.”

In the days and weeks after the attacks, hundreds of people came to help. They came from all over the United States and Canada, and scores brought their dogs. Barry would end up in charge of all the canines volunteering at the site. “It was very confusing,” he said. “During those first weeks, we had more than one hundred dogs. We had to figure out which ones were trained for search and rescue. We told the people who brought their family pets to leave, but some refused. We learned months later that some of these individuals even had the nerve to file claims for injuries they claimed their dogs had suffered while they were working at the site.”

A big part of Barry’s job was to determine which dogs had FEMA training. With the exception of the NYPD and the Las Vegas Metropolitan Police Department, most law enforcement agencies do not send their police dogs for FEMA training, so they are not experienced at search and rescue missions. The dogs who were trained for rescue work were frustrated when they searched day after day and were unable to find any survivors. “You could read it on the dogs’ faces and by their body language that they were just as dazed and confused as we were.”

“At the beginning we thought we’d be able to help hundreds if not thousands of people,” Barry said. “We climbed into every nook and cranny. But even with the dogs, we couldn’t find anyone. All the dogs were getting were body parts or small pieces of tissue.”

Finally, the grim reality began to set in that there would be no one to rescue. At that point the decision was made to call in the cadaver dogs, and they began making a lot of hits. They found thousands of body parts—everything from legs and arms to ears and fingers.

“It’s hard to explain how discouraging that was,” Barry remembered. “We had all kinds of emergency vehicles, ambulances, doctors, nurses, and EMTs lined up for miles waiting to rush victims to the hospital. At the beginning, when we couldn’t find anyone, we were hoping they all got out. It took a long time for us to accept the fact that all of those innocent people had been incinerated or crushed to death.”

* * *

Once Barry realized the work would be mostly looking for body parts so that families and loved ones could have some closure, he felt his job as a captain was to take care of his crew. More than one hundred ESU officers worked the night shift from six in the evening to six the next morning. There were six lieutenants, ten sergeants, and eighty cops on Barry’s team. They spent nine long months at their grim chore.

“Every day started off with a meeting with the city’s Office of Emergency Management,” Barry said. “They would update us on what had happened the day before, which mostly was a list of the bodies they had found. Then they would assign groups of firefighters and cops to work in specific sectors of the site. The dogs were the heroes of this story. They would come across a small clump of dirt and start barking, and it would turn out to be a piece of body tissue. There was no way a human being could have done that. The Medical Examiner took the tissue and identified the person through DNA, which allowed the families to come and retrieve their loved ones’ remains.”

Of the twenty-three New York City police officers and thirty-seven Port Authority cops who died in the attacks, only seven bodies were found. “If we recovered a firefighter, we would call them to take out the body,” Barry said. “They did the same for us. Everyone wanted to carry out their own guys.”

Later, as the magnitude of the disaster became better known and forensic scientists began their studies, people learned that the bodies of the people trapped in the towers mostly disintegrated when the concrete and steel from the buildings fell and crushed them.

There was one spot on West Street where the Atrium used to stand with a massive mound of debris. It took Barry and a team of one hundred officers, working twelve-hour shifts, two months to dig their way to the bottom of the forty-foot pile.

“When we got down there,” he said, “one of the guys yelled up that his dog had found something. The dog was barking at a sheet of metal that was totally flat. We were sure he had made a mistake. One of the cops got a crowbar and pried the metal up, but all we could see underneath was a piece of paper that looked like it was wet. The dog still seemed agitated, and we kept staring at the paper. It’s hard to say how many minutes went by, but at some point someone said they didn’t think it was wet paper. It turned out it was a person’s arm that had been totally flattened under the metal. It made you realize the human body is not much more than a bag of water.”

Barry with his police dog, Harry. “I’ve worked with many great police dogs over the course of my career, but Harry was the best by far at regular patrol work,” Barry said. “He had a sixth sense, an amazing ability to know what posed a threat. That dog helped me send some very hardened criminals to jail.”

The day of the attacks, Sergeant Mike Curtin, one of the most respected officers in the Department, and all of his team but two, perished when the second tower fell. Curtin was one of the first officers on the scene when terrorists mounted the first attack on the World Trade Center in 1993. In 1995 he went to Oklahoma City to assist with the recovery efforts after the bombing there left 168 people dead and 800 injured. Until the September 11, 2001, attacks, the bombing of the Oklahoma City Federal Building was the deadliest act of terrorism on U.S. soil.

The day he arrived in Oklahoma City, Curtin was combing through the wreckage when his eye caught a piece of fabric. It was blue with a red stripe on it. He recognized it immediately. It was a piece of a dress blue uniform worn by Marines.

Curtin had found the remains of Captain Randy Guzman, the officer in charge of recruiting at the Oklahoma City Federal Building. He requested permission to recover Guzman’s remains. The body was in a dangerous spot, and Mike and four others were given only four hours to bring him out. They made it with only a few minutes to spare. While they were freeing the Marine’s remains from the rubble, someone found an American flag, and Curtin draped it over Guzman’s body before they carried him out. The heart-wrenching recovery of Captain Guzman was the lead story in news broadcasts around the country. When a reporter asked Mike Curtin why he risked his life to recover the remains of Captain Guzman, he answered simply that Marines don’t leave their own behind.

Almost a decade after September 11, 2001, Barry is still emotional when he talks about Mike Curtin. “Several days after the attacks, one of the ESU sergeants with engineering experience figured out how to go back and listen to the audio tapes of the cops’ transmissions on September 11. He plotted those transmissions on the blueprints of the World Trade Center and was able to find the place where Mike Curtin and his team were last heard from. Once they pinpointed the spot, the search began.

“I know this is probably hard to understand, but knowing where Mike and his crew might have been during their last moments gave us a lot of hope,” Barry said. “We went down layer by layer, day after day. Seven months almost from the day we started, we found Mike Curtin’s body. He was still dressed in his NYPD ESU uniform and his MP5 was close by. Mike was a hero to me before 9/11, and it was very important to me that we find him.”

Mike Curtin met his wife, Helga, when they were both serving in the Marine Corps. She had come to Ground Zero almost every day while her husband’s colleagues searched for their friend. Even though it was the middle of the night, they waited to remove Mike’s body until Helga arrived with her daughter. As Mike had done for Captain Guzman in Oklahoma City, someone found an American flag and covered the body bag holding his remains before they carried him out with his wife and daughter at his side. Barry is close to tears when he says that finding Mike Curtain is a memory that will always move him. “Since we didn’t recover many of our fallen brothers and sisters, it was very symbolic to at least find one of the most decorated of our heroes. It was also very emotional to see Mike’s wife and daughter there to help carry him off the pile and bring him home to rest in peace.”

* * *

Seeing death up close is part of the job for every law enforcement officer. Then there’s the heartache and suffering they see when they try to help the victim of a violent crime or when someone is killed in a tragic accident. But nothing in their experience prepared the cops to cope with the events of 9/11 and those long months afterward at the site. Barry said the whole thing was like an extended nightmare except you never got to wake up and have it end. The anxiety he felt driving to Ground Zero every day seemed to get worse each day. It was only when he got back to the site and saw the faces of his fellow officers that he began to calm down.

“I thought my job was to keep my guys pumped up, so I gave them a lot of pats on the back and tried to keep them talking,” he said. “There was nothing heroic about what we were doing, but it was serious. A lot of guys lost partners, and they came down when they could. Many of the wives were there every day, too. We all got really close.”

Barry credits the Police Department for their concern about the mental health of their officers who had the depressing job of looking for the remains of the people who had died. But looking back, he now thinks they sent the counselors in way too soon.

“They had counselors down there two days afterward trying to force people to talk about their feelings. When they showed up, we were still trying to find people we hoped were alive. We weren’t about to focus on anything but that until there was no hope we would find them. I told those people up front we weren’t ready to talk to them. We had a mission, and we weren’t done yet.”

As the long sad days turned into weeks and the weeks turned into months, Barry did the best he could to take care of his team. “I tried to keep them talking, but some people just couldn’t open up.” He learned to recognize when someone was becoming dangerously depressed. “When they withdrew, you knew they were getting into trouble. You’d see them sitting there with a faraway look on their face. When I saw that look, I did everything possible to get them to take a couple of days off. In the beginning all of us looked like that, but most of the cops down there were resilient, and eventually we got caught up in the distraction of the work. But there were others who didn’t do so well. Those were the people you worried about.”

On June 1, 2002, the city officially shut the site down. Teams of firefighters and cops had worked tirelessly for nine grueling months to find the remains of the close to three thousand innocent victims who had perished.

With his work at Ground Zero over, Barry went back to the Emergency Service Unit, which was unusually busy. As a Captain, along with his regular workload, he shared responsibility for security at the Republican National Convention during the summer of 2004. In addition, his bosses put him in charge of planning the security arrangements for the President during the time he was scheduled to attend the convention. He was also in charge of the FEMA Urban Search and Rescue Team and worked with the FDNY to rebuild the team that had lost so many of their members on 9/11. There was a lot to do, and he did not have the time or energy to focus on the attacks and the nine months he had spent looking for bodies at Ground Zero.

In 2006 Barry retired from the NYPD. It was not long after that before the emotions he thought were buried came flooding back.” I was exercising a lot, and my new job as security director for the United Nations Plaza complex was demanding. I was busy. But every time I heard or saw anything about 9/11, I would completely break down. That’s when I decided to seek professional help.

“It was during my visits to the counselor that I began to understand what we had all been through,” he said. “A sudden death or bad accident or act of violence is one thing. It’s usually over in an instant, and you can slowly recover with time. But there were a lot of us who worked at Ground Zero, walking that pile every day, looking for remains of our friends who had died, finding more body parts or even just small pieces of tissue, then calling the Medical Examiner to come and take it away. We had to deal with it over and over again.”

Barry’s therapist told him that, to her knowledge, there had never been an incident in which first responders had to go back, day after day, week after week, month after month, to the scene of a terrible crime where thousands of people had died. The endless wakes and funerals only added to the extended emotional trauma. Barry attended over forty funeral services for close friends and colleagues in those first months after the attacks. There was no way to escape from the sadness and grief, so he buried it deep inside.

In talking it out with the therapist, Barry began to understand that the stress he was under had taken its toll on his family. His decision to sleep at Floyd Bennett Field so he could be closer to the site meant he did not return home for weeks. He shut out his wife and children by not talking to them about what he was going through. The few times he did go home when he had a day off, things did not go well.

“I remember my first day off,” Barry said. “I couldn’t sit still. I kept calling my guys, asking them if they’d found anything. My wife kept staring at me while I was on the phone. After a few hours she told me to go back to work. She said it was obvious it was where I wanted to be. So I left and went back to the site. It was my first day off, and I was so restless I could not make it through a whole day at home.”

“The bonds we formed over those months working at the site were extremely close, but they worked against us, too,” Barry said. “On our days off, we didn’t know what to do with ourselves.” When he did go home, his wife kept after him to talk to her, but he just couldn’t open up. Ultimately, their marriage did not withstand the stress, and Barry and his wife filed for divorce.

“My middle son, Daniel, had just started college in September 2001. He knew we had lost fourteen officers from Emergency Service, and I think he understood how hard that must have been on me.” Barry was shocked when Daniel called him and announced he was dropping out of school so he could enlist in the Navy. Barry’s older son, Chris, was in the Navy Special Forces, and his younger brother wanted to join him.

Barry is proud of his children. Chris went to the Persian Gulf with the Special Boat Unit, and Dan later served in Iraq as part of the Special Reaction Team. His daughter, Patty, is an elementary school teacher and is married. They have a daughter, Emma, Barry’s first grandchild. His youngest child, Matt, works for UPS and is thinking about a career in law enforcement.

* * *

“Looking back I realize the Department should not have kept the same people down there for nine months. They should have sent us home and ordered us to do it. When there was a choice, virtually no one made the decision to leave. Emotions were running strong that we had to find our brothers. I can still hear their voices when I asked them if they wanted some time off. Everyone had a buddy or partner they were searching for. They’d say, ‘I’m not leaving until we find Tommy Langone. I’m looking for Vinnie Danz. I’m not going until I bring Mike Curtin home.’”

* * *

Almost a decade after the attacks of September 11, the New York City Police Department has changed dramatically. A substantial portion of its annual budget of $3.7 billion is now devoted to the counterterrorism mission. The Department requires higher-ranking officers to attend lectures and courses on everything from the inner workings of Al Qaeda to how to recognize a potential suicide bomber.

Barry remembers the weeklong course he had to take on bioterrorism. “It was only a month before September 11. One day the professor came into class holding a small vial. He told us to look outside at the clouds and then discussed what a great day it was for a biological attack. He said he could wipe out the whole city with the contents of that one vial and that the clouds would keep it from dispersing. The whole thing seemed crazy.”

Two months after that class, Dan Rather received an anthrax-laced letter, and Barry was on the team that went to the offices of CBS to investigate. “To this day, we still don’t know who sent that letter,” he said.

A few weeks later, when the NYPD needed to establish protocols for police officers responding to calls where biological, chemical, or nuclear materials had been let loose, they put Barry in charge of the project.

* * *

Today the NYPD is a sadder place. The ongoing fallout from the attacks hit many police families hard. Divorce rates are up, and exposure to the toxins at Ground Zero has taken a toll on the people who worked at the site for all those weeks and months. Hundreds of officers assigned to the Emergency Service Unit retired in the first few years after the attacks. Some left the job well before their expected date of retirement. The exodus left ESU with fewer experienced officers to mentor the newer members of the team.

In December 2006 Barry made the difficult decision to retire from the NYPD. He’d received a call from the Chief of Patrol that he was being transferred out of ESU. The Chief told him his experience was needed elsewhere. Barry panicked. Everything he had experienced since being assigned to Emergency Service came rushing back to him: the perp searches, the barricaded EDPs, the bridge rescues, the gang takedowns, the counterterrorism assignments, the President’s motorcade details, the New Year’s Eve details, the FEMA Urban Search and Rescue Team, the K-9 training, and the nightmares and memories of 9/11. It all came back in waves of emotion.

“I felt like my life would be over if I was transferred out of ESU,” he said. “I had been through hell with those men and women, and I could not imagine working anywhere else. I guess I felt a sense of security and a feeling of family working in ESU that I knew could never be replaced. I had suppressed many of the nightmares of 9/11 by working nonstop on counterterrorism assignments. I never had time to unwind. I just kept going at one hundred miles per hour. Now my life was crashing to a stop. It was like hitting a brick wall. They were taking away my family, my friends, my colleagues, many of whom had worked side by side with me at the World Trade Center. They didn’t understand what Emergency Service meant to me. I tried to speak with several chiefs about allowing me to retire from ESU, but they didn’t seem to understand what it meant to me. They’d never worked in ESU, and they didn’t get to experience the things that I did. After speaking with the Chief of the Department and accepting the fact that he wasn’t going to keep me in ESU, I went to the pension section and began the process to retire. It would take time to finalize, but my career with the New York City Police Department was over. There is a saying about ESU that makes it so special to those of us who were lucky to wear the uniform. ‘When the public needs help, they call the cops. When the cops needs help, they call ESU.’ It was a ticket to the greatest show on earth.

“Once I retired, I went back to school to get my degree in homeland security management. It just seemed like the logical choice after my career with the New York City Transit Police and the NYPD and my degrees from the FBI National Academy and Police Management Institute. I also started working as the director of security at the United Nations Plaza. I was recruited for the job by a company that trains and deploys explosive detection dogs, and many of their employees were current or former NYPD K-9 Unit and ESU members. The job is very interesting and I got to meet many dignitaries while working closely with the State Department and Secret Service and protecting several missions to the UN. But the reality for me was, nothing would ever compare to a day in the life of an ESU captain.”

* * *

A close-knit group — Front row, L to R: Parents Lenny and Trudy, sons Matt and Chris. Back row, L to R: Jackie Bourne, Barry, sister Patty with her daughter Emma and son Dan.

Despite all the trauma from the aftermath of the terrorist attacks and his demanding job with a lot of responsibility supervising forty employees and four bomb dogs at the United Nations Plaza, Barry says there is not a day that goes by when he doesn’t miss the NYPD.

“When I was at the UN, someone from Emergency Service stopped in to visit me at least once a week. They filled me in on what was going on. They are great people, and I miss them. And I miss the work. Every day of my life, at least a couple of times a day, I want to be back there.”

Excerpted from Brave Hearts: Extraordinary Stories of Price, Pain, and Courage by Cynthia Brown, publisher of American Police Beat. Available at Barnes and Noble, Amazon, and at www.braveheartsbook.com.